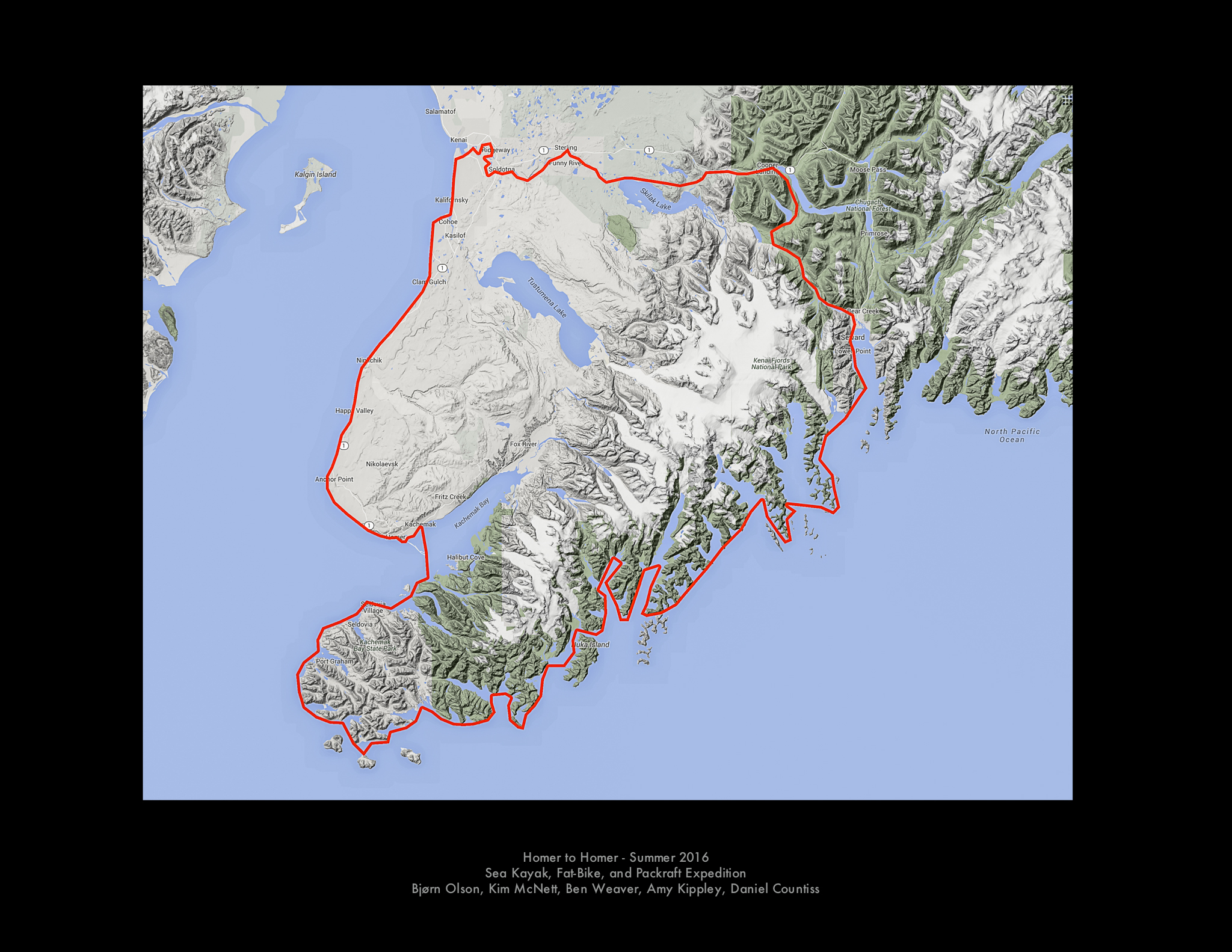

On the evening of summer solstice, 2016, Kim McNett and I launched our sea kayaks from our home in Homer and spent the next month exploring our "back yard". Our kayak route took us to Seward where we joined our bikes, backpacks, packrafts and three friends, and continued overland onto Cooper Landing, Kenai and finally back to Homer.

Logistics, for Kim and I, were straight forward: drive the bikes to Seward, leave them and the rest of the overland gear with friends, drive home, cram as much food as possible into the kayaks and launch. With roughly three-weeks of provisions we planned to explore deep into the fjords, bays, and islands. The outer gulf coast, we predetermined, was not a place to rush past.

Our first full day of kayaking, and still within Kachemak Bay, we were beset upon by a pod of humpback whales. As two surfaced near me another swam under Kim and flicked her with its pectoral fin. From that moment the tone for the trip was set and every day thereafter was filled with wildlife, a healthy tinge of excitement and an abundance of rugged beauty.

The coastline between Homer and Seward is arguably one of the best sea kayaking trips in North America. Sheer granite cliffs - some of which rise over one thousand feet straight from the water - strain your neck, and tidewater glaciers, intertidal lagoons, powerful tidal currents, tide rips, swell, rock gardens and surf beaches, plus astounding wildlife, all cram into this magical slice of Alaska. Over our three-week trip we counted fifty six species of birds, saw wolf, black bear, mountain goats, three species of whale, seals, sea lion and sea and river otters.

A strong following sea surfed Kim and I the final miles into Seward and moments later we were whisked into my brothers van. His cover band, The Moosefits, were playing a show for a friends birthday later that evening. After three-weeks on the water we were ready for showers, beer, friends and a punk-rock show. Natural serenity and hard-core music are not disparate in my mind and yet it was clear that a new chapter of our summer trip had ended and we ramped up for the next.

The following day we met our friends Ben and Amy at the Seward train depot and a few hours later our Homer friend Daniel Countiss drove into town. Under a warm sun in a friends front yard the five of us began packing gear, loading bikes and pouring over the map.

We'd met Ben and Amy last fall at Salsa Cycles Ride Camp, in Wisconsin. Kim and I had been invited to the three-day event to give a presentation about wilderness adventure cycling in Alaska and over the long weekend we began loosely talking with Ben about doing a trip together. After months of emails and Skype conversations we were finally ready.

Three distinct chapters marked our route from Seward back to Homer: the Resurrection River Trail to Cooper Landing, the Kenai watershed to the city of Kenai, and the long, uninterrupted beach - ideal for fat-biking - between Kenai and Homer. Over the next eight days we peddled, pushed and paddled our way through "Alaska's Playground".

Each of these methods, or disciplines, of travel - the sea kayak, fat-bike, and packraft - require distinct skill sets but, for me, they all share a commonality: they are each modes of efficient human-powered transport over a wide range of terrain, and they allow the practitioner a wide breadth to make the traveling as fun as they wish. Over the course of this month-long trip we rarely over-concerned ourselves with daily mileage but rather sought out the most interesting lines and would often dally at the rock gardens, surf spots, log-rides, eddy lines, deep creek crossings and technical beach cobble on the bikes. Forward, always forward, but as fun as possible.

One evening around the camp-fire someone asked, "Why do you do these kinds of trips?" For me, the answer is both simple and complex. The simple answer is, 'because someday I will die and I believe life is worth living.' But, the more complex answer has something to do with finding a niche in the world. When someone spends more than a little time in nature they typically can't help but see that each animal fills a gap and utilizes its time and space in a distinct way. The impact I leave on the landscape is minimal but the impact the landscape has on me in immeasurable.

We rode the last cobbled stretch of beach back to our cabin almost a month to the day after leaving and proceeded to awkwardly high-five in a five-way cluster. Our skin chapped and burnt from the days of sun and cheeks sore from laughing; our batteries fully recharged.