This article originally appeared in the Homer Tribune.

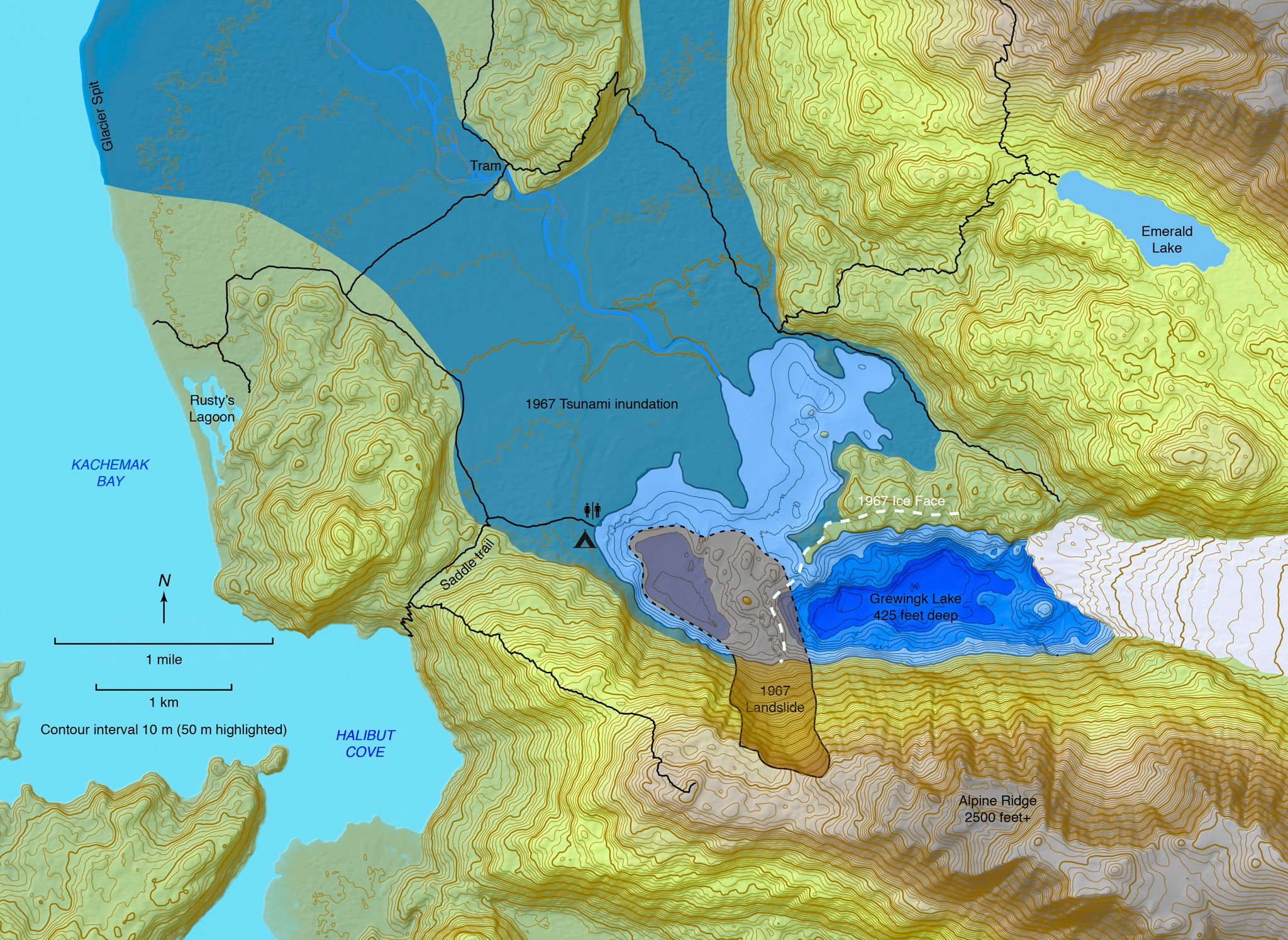

Imagine hovering in a helicopter above Grewingk Glacier Lake, in Kachemak Bay, fifty years ago. From this safe vantage, you watch as 80 Empire State Buildings worth of material, slowly dislodge from the steep slope above the lake, and then let go all at once. Cleaved from the surface, you see the unfathomable volume of material gain momentum. By the time the deafening roar reaches your ears, the 110 million cubic yards of rock has thundered into the lake, sending a wave hundreds of feet into the air. Craning your neck, you watch this fast moving bulge of water slosh over the outwash plain, uprooting alders and mature trees, carrying everything in its path all the way to Kachemak Bay, more than four miles distant.

You just witnessed a suite of natures most destructive and incredible phenomena—a landslide generated tsunami.

This may seem like a crescendo scene from an apocalyptic Hollywood movie, but last October marked the fifty-year anniversary of the Grewingk landslide and tsunami.

No helicopter hovered in the air and thankfully no one was in the valley that day. However, many in Homer and nearby Halibut Cove heard the crash and later witnessed glacier ice in Kachemak Bay. Homer residents were able that fall to salvage trees for firewood that washed ashore onto the Homer Spit.

This event has captured the attention of two local geologists, who worry another landslide and tsunami could occur in the same area with similar, or worse, devastation.

“The rock all along the mountainside is highly fractured and faulted, as is the rock generally in the Kenai Mountains,” geologist Ed Berg said about the slope above Grewingk Lake. “Major rockfalls or landslides could probably occur anywhere along the steep slope of the mountainside.”

Seldovia resident and tsunami hazards expert Bretwood Higman added, “The combination of steep slopes and weak rock is the perfect recipe for a big landslide. Additionally, the 1967 landslide shows this area has the potential for very large landslides, and this potential may be all the greater now, since the glacier has retreated a lot in the past fifty years.”

Throughout coastal Alaska, landslides, some of which have caused massive tsunamis, are occurring with increased frequency. Steep mountain valleys, fjords, and bays that have, for many thousands of years, been full of glaciers have seen rapid retreat over the last fifty years. This has led to slope instability in many areas. Glaciologists and geologists call this process, glacial debuttressing.

“The slopes above Grewingk Lake are notable because they are much steeper than most slopes in the area, and they're not more strong,” noted Higman. “They probably are so steep because they were supported by the Grewingk Glacier until recently, and because the glacier has been actively undercutting them. The combination of steep slopes and weak rock is the perfect recipe for a big landslide.”

In June, Berg, Higman and the American Packrafting Association organized a human-powered research expedition to Grewingk Glacier Lake, hiking over the trail with a flotilla of packrafts and some low-budget tools.

One of the goals of the group was to better understand the depth of the lake. This information is key to understanding the potential for another tsunami.

For the trip, Berg engineered a simple 1x4 contraption, which he affixed to the stern of his packraft. From this device he mounted a borrowed sonar fish-finder to measure and record the lake bottom depth profile. Others in the party used less sophisticated instruments to measure lake depth from the platforms of their packrafts, like a handheld sonar depth gauge or weighted lengths of string.

The deepest spot the team discovered—490 feet—was near the glacier face and the average depth below the potential landslide slope averaged 360 feet. “We were surprised that the lake is so deep,” said Berg. For a landslide tsunami, deeper water means greater hazard. The entire volume of the landslide could end up beneath the water‘s surface—creating a much bigger wave. Deeper water absorbs more of the landslides energy, converting it into a bigger, more powerful wave.

But how likely is such a landslide? Berg and Higman both agree that further study is necessary, including a detailed survey of the ridge above the lake. “In particular,” Higman says, “I'd look for roots that are stretched across cracks, or signs of blocks that have shifted down as cracks opened below them. If such signs are apparent up there, that would be a "red alert" situation, suggesting dramatic action like closing trails.”

Higman would also like to see computer modeling of landslide tsunamis to assess areas within the valley, which are most at risk for visitors to the area. Furthermore, computer models could resolve the potential for marine tsunamis in Kachemak Bay. “The marine tsunami risk is likely very minimal,” says Higman “but may be relevant since even a small marine tsunami could be very damaging to the Homer Harbor.”

Thus far, Berg and Higman have been aided with small equipment loans and organizational support from the American Packrafting Association but the two are working without funding or institutional backing.

“We would like to see some monitoring program put in place,” says Berg “that could provide timely warning of a future collapse and tsunami.”

“University researchers could be great, especially if they worked with us locals,” said Higman. Adding, “I'd like to see some funding to support someone to take the next steps, including assessment of the hazard, public outreach, investigating monitoring, [and] coordinating different research efforts.”

Statistically speaking, there is no good reason not to visit Kachemak Bay State Park’s magnificent treasure, the Grewingk Glacier. It’s not advisable to camp on or near the lakeshore but the likelihood of a cataclysmic event occurring during a day hike through the park is quite low. No one can predict when or even if there will be another landslide and tsunami. As our climate continues to warm, the research and study of these interconnected phenomena is wildly important—as important, perhaps, as visiting an Alaskan glacier.

-Bjørn Olson