The author shuttling a load of gear and a hindquarter of caribou.

When summer’s vegetation turns from green to yellow, an ancient instinct takes hold; autumn is the harvest season. All northern creatures—the bear, squirrel, muskrat, ermine, ptarmigan, porcupine, moose, caribou, and more—all know, deep in their genes, that winter is coming. Human beings, still emerging from the Ice Age, and poorly adapted for modernity and civilization, also feel the compelling siren call to store up calories for the coming cold and dark.

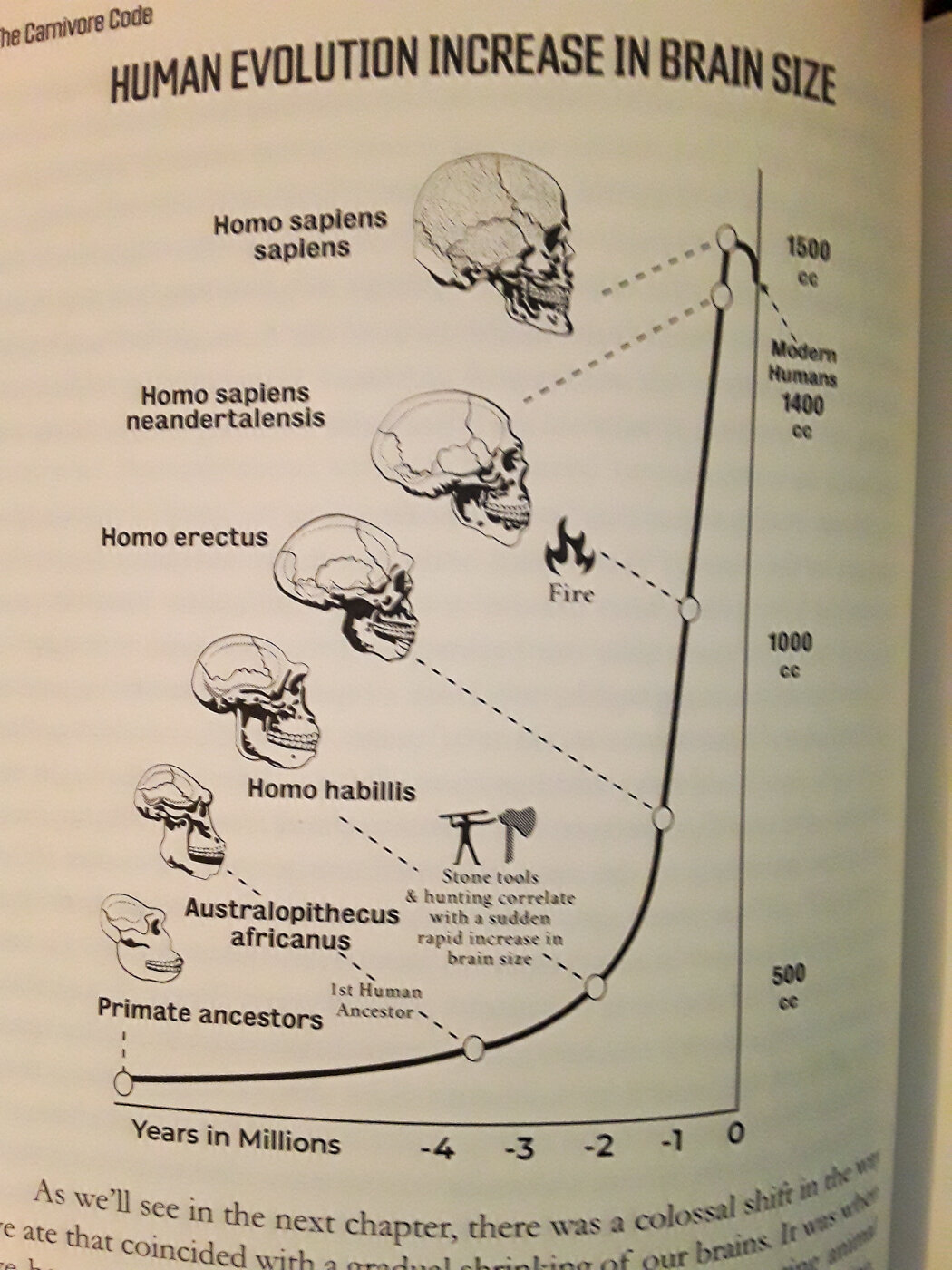

In the first week of September, my fiance, Kim McNett, my brother, Clay, and my long-time best friend, Mark Teckenbrock, and I caravanned from our homes in southern Alaska into the interior of the state to hunt caribou by human power. We would ride bikes with trailers into the enchanted mountains of the Alaska Range, camp, catch grayling, drink cold water, wake up early, try to outmaneuver cunning and fleet-of-foot creatures, and rekindle our ancestral genes. Our two and a half million years of hominid, hunter-gatherer evolution hungered for the opportunity to be expressed.

On our fourth day, my friend Mark and I crawled along the rain-soaked tundra on our hands and knees, gently sliding our rifles ahead of us. The two caribou we’d been watching through our binoculars and stalking for the last several hours were now just a couple hundred yards below us. Vibrant red and yellow leaves of a dwarf willow bush offered us a blind. The caribou approached the base of the hill, from the wide valley beyond, and then disappeared below us. They were close. We waited.

Five minutes passed. Then ten. Finally, I began to fear they may have wandered away unseen. I slowly crept up into a low stoop to peer over the edge. Barely breathing, I scanned right and then left. I froze. “They’re right here,” I whispered, pointing with my eyes.

For each of the previous days, our little band had been stealthily stalking the cagey and nimble animals. We were in the caribou’s kingdom and they were on high alert. My routine had been to crawl out of the shelter at the first hint of light, quickly fill my thermos with coffee, grab my rifle and binoculars, and hike uphill.

Several times, my pursuit of a handful of small herds had been close, but with few blinds and no trees for cover, my presence startled them away. By mid-afternoon, I’d walk back down to camp to break my fast, dry out near the fire that my brother diligently kept going, despite the rain, and regroup with the others. After a break and a meal, I’d head back out again. On the third evening, I realized it was time for a new strategy. We decided we would all hunt together as a group and try a new area further up the valley the next day.

Growing up in Alaska, wild fish and game and foraged berries and mushrooms have always been an integral component of my diet. As an adult, I’ve tried to make harvesting this wild food a part of my annual routine, but work, fat-bike and sea kayak expeditions, and other life distractions often compete for our time and attention. This year, the two expeditions Kim and I had planned had to be put on hold due to the pandemic. This fact, coupled with a newfound interest in ancestral nutrition, led Kim and me to focus more of our energies on wild harvesting.

Global warming is affecting Alaska at more than twice the rate as the mid-latitudes. Often, our human-powered adventures through Alaska deepen our insights into these startling changes that are occurring. We don’t, however, have to travel far from home for evidence. In the summer of 2019, record-breaking temperatures swept across the state and a series of wildfires wrought apocalyptic havoc across the Kenai Peninsula and beyond.

We began our harvest season this spring in the burnt rubble leftovers from the 167,200-acre Swan Lake fire, just north of our home. Morel mushrooms often fruit after a fire, and fruit they did. We filled up with gallons upon gallons of this highly sought-after fungal delicacy.

After mushrooms, we switched gears to harvesting salmon and other fish. Alaska boasts of intact and mostly healthy salmon populations of all five species. In our region, two species are abundant enough to allow for commercial and personal use fisheries, as well as sport fishing. Sockeye (red) salmon are the staple in our region. Management of our personal use fishery allows for the use of hyper-efficient dip nets for Alaskan residents. Coho (silver) salmon run later in the season, and in our area, there is a personal use set net fishery, which allows an individual to catch 25 per person, plus 10 more per household dependent. We rounded out our salmon harvesting with a few Chinook (king) salmon, which we caught with rod and reel.

Taking cues from Alaska’s First People, I have begun to deepen my understanding of the health of our local ecosystems by directly relying on it for sustenance. One becomes acutely aware of the seasonal changes, migratory patterns, health of individual species, the air, water, and soil conditions, and more when relying on wild-harvested foods. These insights, coupled with the wisdom of elders, fish and wildlife managers, and others, helps establish a connection to place and an awareness of its health or its disease and or misuse.

In Alaska, 95% of the food found in grocery stores is imported from out of state. This importation comes at a high ecological cost, which is never factored into the price at the supermarket. Much of this food, produced halfway around the world, is also grown in nutrient-depleted soils, fertilized by petrochemical fertilizers, and often sprayed with glyphosate-based herbicides. Industrially raised livestock is pumped with hormones, antibiotics, and fed a diet of GMO grain, which radically alters and diminishes its nutritional value.

Since 1991, the rate of obesity in Alaska has more than doubled, from 13% to 30% of our population. Type 2 diabetes has also more than doubled over the same period of time. For thousands of years, however, Alaska’s First People lived off this land and were beacons of health, strength, and endurance. That condition of vitality, coupled with a sense of connection to place, is what I am passionately seeking in my own life.

The sturdy caribou and I locked eyes as I slowly lowered myself back down and gently picked up my rifle. Many Alaskan Native stories tell of how certain animals will offer themselves to a hunter, but I was mystified that the creature was not bounding away from us. Rather than fleeing at the sight of me, the caribou walked toward us. Squinting with one eye and peering with the other through my rifle’s scope, I consciously focused on calming my breath. Its chest filled the optical loop. The caribou then turned profile and stood still, offering me a clean shot.

Moments later, Mark walked back uphill to inform Kim and Clay of our success and enlist their help. I embraced the moment to be alone, and to offer my solemn thanks to the caribou. After the violent outburst from my rifle, the valley was again silent. I knelt down beside the fallen animal and let a wave of emotions wash over me.

When Kim, Clay, and Mark returned, I was reminded of the advice my brother and I had been given as children by our godmother, Umara. A Siberian Yup’ik woman, Umara grew up in a pure hunter-gather culture, in the middle of the Bering Sea. She told us that it’s essential to offer a dispatched animal a drink of water for its journey toward the other realm. We each felt the solemnity of the moment as we offered thanks and gave the caribou a farewell drink.

Whenever we consume food, it comes with a cost. That cost, more expensive than money, is most often invisible and not accounted for in the marketplace. As we further our understanding about the consequences a global economic system—in conjunction with a perpetual growth model, on a finite resource planet— is having upon the natural world, I believe it is important to find ways to reduce these hidden costs as much as possible and to find alternatives. What we saved, in this instance, is an enormous carbon footprint for a less valuable and less nutritious substitute. There are few middle-men or egregious carbon outputs that stand between a hunter, a wild-harvester, or a gardener and the food they procure. When these engagements are undertaken by human power, the negative externalities drop even further. Our biggest cost was effort and a willingness to do what many would consider the “dirty work.”

Alaska has a 21st-century economy, but we still have a 19th-century environment. This slice of the world has maintained its genuine wealth because the focus on what is most valuable has, for the most part, remained intact. Salmon, moose, berries, mushrooms, crab, halibut, and the ecological conditions that support these creatures, and many more, still exist here. But, there is no guarantee this will always be the case. When more people learn to cherish what nature provides, by making an effort to become a part of it, maybe then we’ll learn, or perhaps remember, how to be better caretakers. Wilderness is a place; wildness is everything, including us.

With sharp knives and a bone saw, we portioned the field-dressed caribou into thirds and, along with the organs, packed them into cotton game bags. A short walk brought us back to our bikes, where we loaded the trailers and tightly lashed down our sacred quarry for the ride back to camp.

That evening, we feasted on some of the world’s most nutrient-dense and delicious food. Frost was in the air as the light fell and the stars came out. We warmed our bodies around the roaring willow fire as we recounted the day. Within each of us, a different and much more ancient fire was being rekindled.