Beargrease meets bear

A turning point, in the not too distant past, was crossed without my fully noticing it. My life as a cyclist has been largely one of cobbling parts together from one old beater to the next, with the occasional splurge on a fancy component. Now I find myself riding a 23-pound carbon fiber Salsa fat-bike.

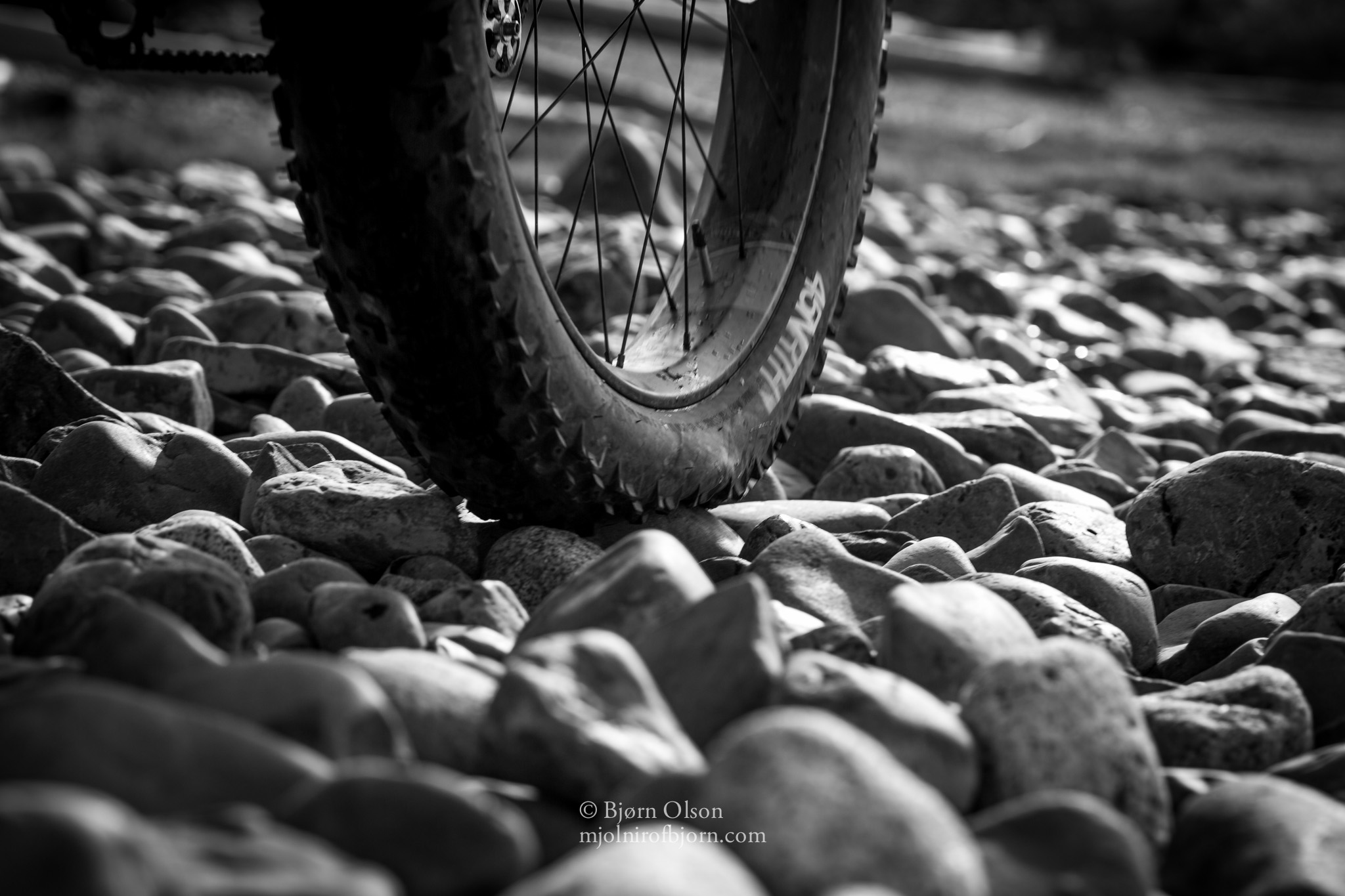

The first thing I noticed about the Salsa Beargrease, once I assembled it and took it for the first spin, was the how light it felt underneath me. My immediate playground is the beach below my cabin, which is comprised of technical slabs of shale, seams of coal, loose gravel, big boulders and sand. I love riding this stretch of beach because it requires attention and focus to navigate and no two rides through are ever the same. Upon the Beargrease, it was a whole new experience of delicate maneuverability.

A lightweight fat-bike feels unstoppable on rough terrain.

The idea, as I understand it, is that fat-bikes should float. In terrain where traditional mountain bikes would wallow and sink, a fat-bike comes to life. It stands to reason that a lighter fat-bike will perform better in soft riding conditions and so far this is proving to be true.

The core of my interest and motivation is expeditions – long wilderness routes where self-reliance, adaptability, and creativity are required. I love technical riding for the confidence it builds. I love micro-adventures for the habituation and preparedness it heightens. I love commuting for the daily dose of lactic acid and the feeling of wellbeing that comes from hauling myself around under my own steam. However, in the back of my mind these excursions are all mental and physical exercises for next big trip.

Tucked in for the night.

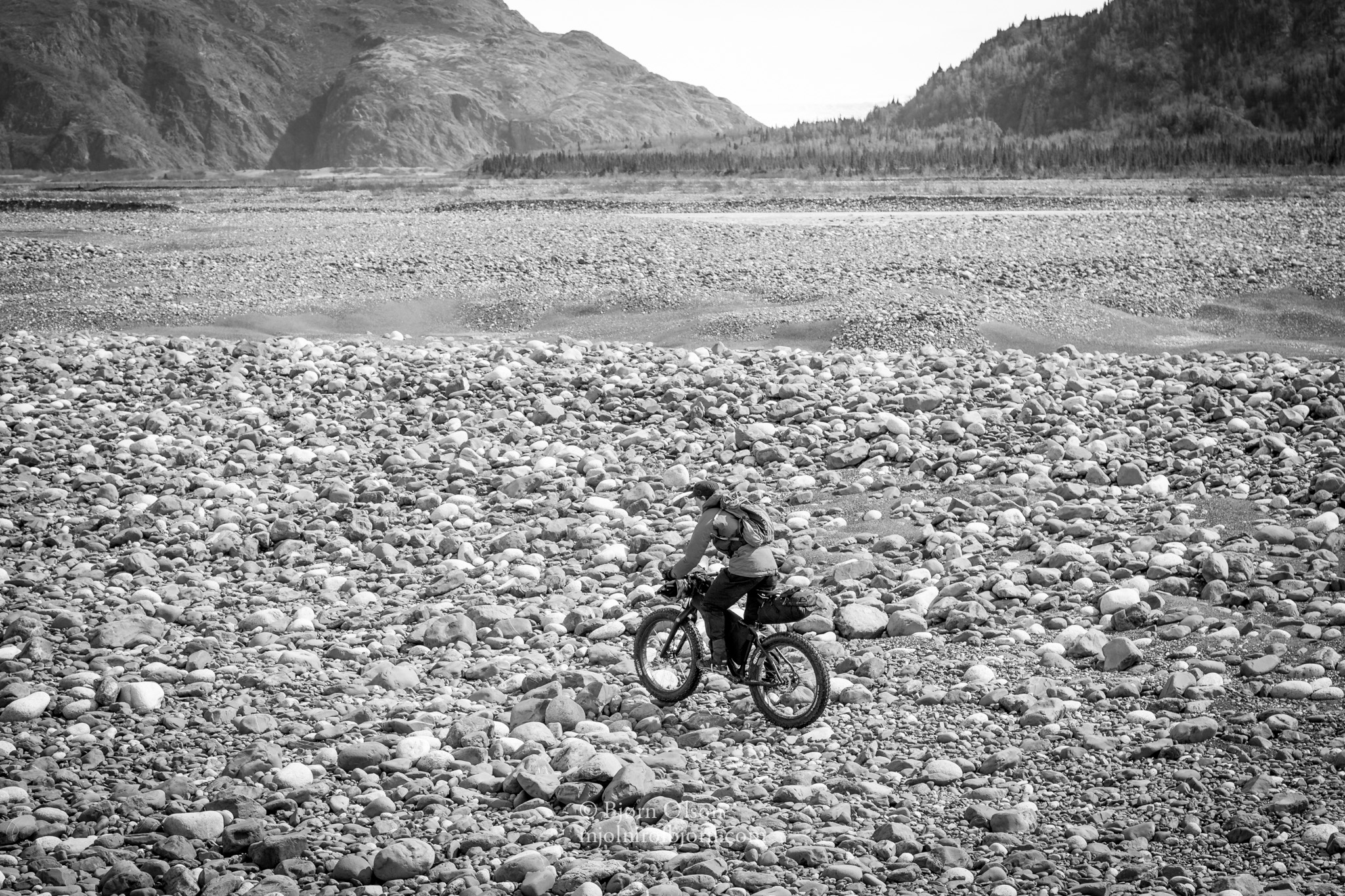

Last week my partner Kim and I spent 5 days bikepacking with the new bikes. Our goal was to mimic the conditions we expect to encounter on our upcoming six to eight-week wilderness expedition. We wanted soft, technical terrain with a water component and occasional bikewacking/hauling. We found what we were looking for, and in both our estimations the Beargrease gets an A+.

It is often stated that steel is the best choice for road touring. One of the reasons is because if anything should crack on the frame it is the easiest material to repair. I don’t foresee myself carrying a welder anytime soon but I can envision carrying sandpaper, rubbing alcohol, two-part epoxy and carbon fiber patch material. My hunch is, this repair kit will remain unused and at the bottom of the pack but there is no other frame material I am aware of that someone in the middle of nowhere can field repair as readily as carbon fiber.

Ready for assembly after a short trip in the packraft.

In and out of the packraft with the bike takes a minute no matter how efficient you are. Through axles are not only stiff and secure, they also shave time during the wheel on and off transitions that occur regularly on summer bike/raft trips. Leaving the axle in the fork with the wheel off also seems more secure and sturdy during transport.

Another feature, which I approve of, is the lack of attachment points on the bike. There are no water bottle cage or rack mounts and in this instance I think this is a good thing. Our plan is to use two or three Relevate Designs bags on the bikes while underway this summer but we will also be carrying large Mountain Laurel backpacks. We intend to take all gear off the bike when we are bushwacking or are otherwise unable to ride. When conditions become favorable we’ll strap the bags and packraft back on. Holes in the frame in this instance will just be places for water to get in which would add unwanted weight and corrode moving parts.

Kim crosses a shallow creek.

One five day trip and several weeks of riding around on the Beargrease have led me to believe that I’ll be comfortable for the long haul. Now that all the micro-adjustments to the bike have been made, the tires have been kicked and several coats of mud have been applied, it feels like it’s mine, and it feels ready for adventure.

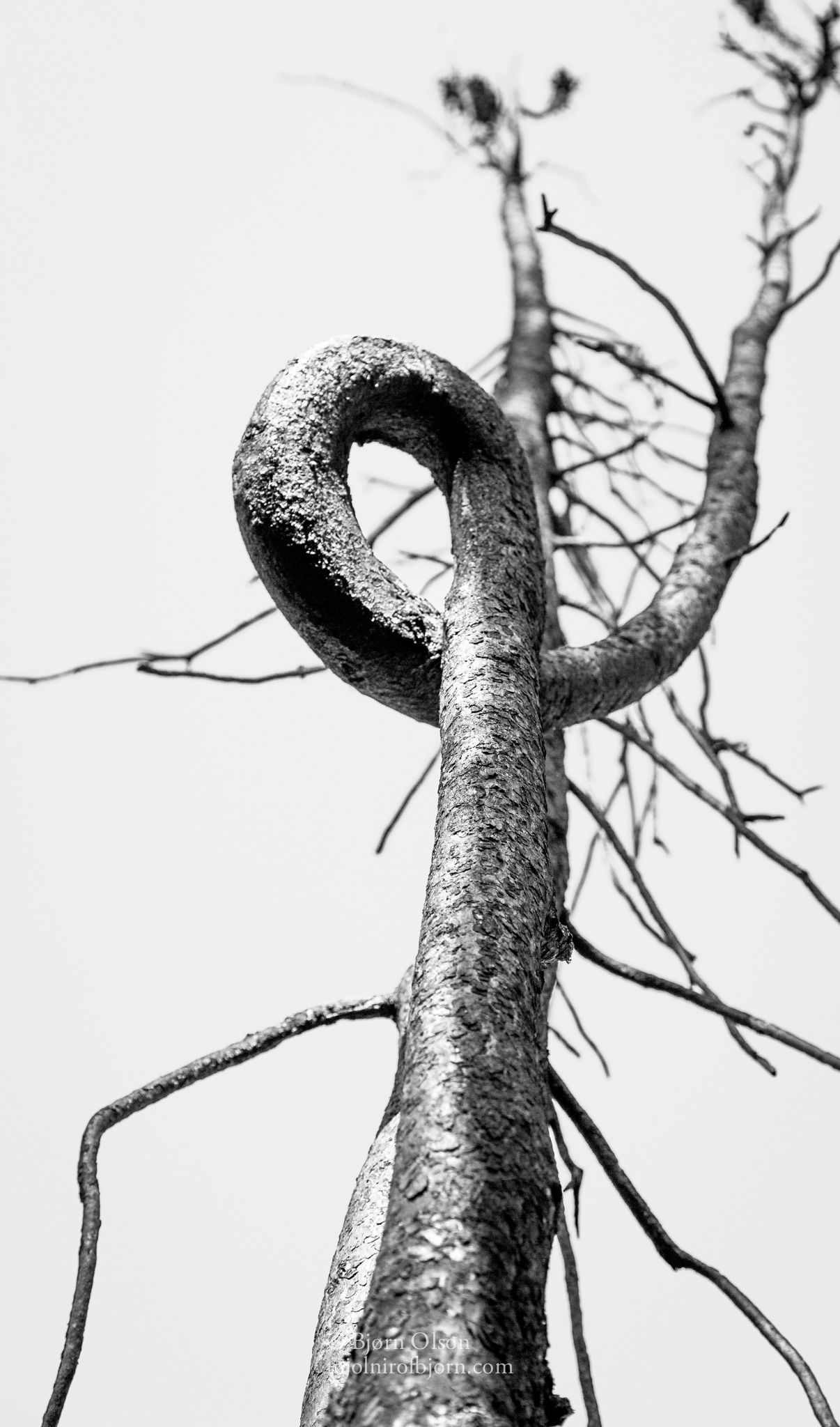

Simple and elegant.