In 2018 I attended the Alaska Forum on the Environment and was interviewed by Story Corps. Here is the full-length interview.

Click HERE for the interview.

https://archive.storycorps.org/interviews/cte000037/

Your Custom Text Here

In 2018 I attended the Alaska Forum on the Environment and was interviewed by Story Corps. Here is the full-length interview.

Click HERE for the interview.

https://archive.storycorps.org/interviews/cte000037/

Fried Bowhead muktuk that the team was gifted in Tikigak (Point Hope), which helped fuel their expedition.

Walking down the unfamiliar school hallway, my ears led me toward the cacophonous gymnasium. As I crossed the threshold into the bustling space, I paused for a second, allowing my brain to re-calibrate. I’d just spent two weeks in the Arctic wilderness of Alaska. The flickering fluorescent lights, strong odors of wild-caught food, and the sound of over a hundred voices bouncing off the walls, pile-driving all at once into my ear canal, was a stark contrast.

Just after summer solstice, my girlfriend Kim and I, along with two of our adventure pals, had set out from Point Hope, with expedition-loaded fat-bikes. Our goal was to become the first people to fat-bike from the village, across the top of Alaska, to Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow). We’d endured a three-day storm with wind speeds up to 100 miles an hour, but we’d also been treated to spectacular conditions, abundant wildlife and some of the most remote terrain I’d ever experienced. When we arrived at Point Lay, known locally as Kali, the first village along our 400-mile route, our bodies were running on fumes. We desired a resupply and advice from locals about the way ahead.

“Welcome to Kali,” a sweet Inupiaq elder with a bent spine said as he lifted his soft hand to mine. “Come in and eat. Today is Nalukatak - the whale festival.”

The gymnasium had been transformed into a mess hall - outfitted with school cafeteria folding tables covered in butcher paper. Blue tarps lined the floor, protecting it from errant drips or spills. A string of serving tables lined the far wall, piled with pots, disposable aluminum platters and five gallon buckets bursting with food. Paper plates, jugs of juice, carafes of coffee and tea crammed into every bit of remaining space on the overburdened tables.

I peered down the isles of seated locals looking for my teammates. I found them seated at the far end of the gymnasium, map already out, engaged in conversation with a man whose calloused finger pointed out landmarks. “This is Doug Rexford,” Kim said. “He’s the captain of the whaling crew.” We were invited to sit and eat with him - the praiseworthy leader at the table of honor.

The day before our little cadre arrived in Kali, we’d seen an enormous pod of beluga whales – the most any of us had ever seen at one time. The local hunters had seen this pod too. Using contemporary means yet millennia-old hunting techniques, they herded the pod with their skiffs to the inside of a lagoon and dispatched the number of animals they needed to see the community through the long, cold winter ahead.

“Would you like some boiled beluga muktuk,” a woman standing behind me, holding a 3-gallon pot and ladle asked me. “Quyanaq. Yes, please.”

Growing up in Interior Alaska, our closest family friends were from the Siberian Yupik village of Gamble. Through many shared meals, I’ve eaten a lot of bowhead whale and had tasted beluga before but this was to be my first experience eating it boiled.

“The boiled muktuk is best when the beluga is fresh,” Doug told me as I picked up a one-inch cube of the warm blubber and skin layer - a circumpolar mainstay and calorie-dense treat. My teeth effortlessly fell through the substance, oozing a smooth, rich oily flavor throughout my mouth. I closed my eyes and slowly chewed, savoring every molecule. Before reaching for my second piece, I offered my impression: “To say that boiled beluga is like butter is a disservice. They should say that butter is like boiled beluga, but not as good.”

Over the next several hours, we glued our trail-worn bottoms to the cafeteria seats and relished one course after another. As soon as the swan soup had been served and consumed, along came someone dishing out caribou ribs or seal steaks or dried whitefish with seal oil. The waitrons walked the aisles, filling every plate or bowl, always serving the elders first, until each offering was finished.

Our wind chapped faces glistened with grease and a surge of nutrition flooded our hungry mitochondria. The food that had supported our host’s ancestors in this severe Arctic environment was exactly the fuel we needed to continue our journey.

The following day, as we rode away from the village, armed with insight, encouraged by new friends, and loaded down with leftovers I sucked my teeth seeking out any overlooked morsel.

Musk ox skull between the abandoned village of Bering and Teller, Alaska.

It would be absurd to attempt a retrospective of my last decade. There are a few general points or highlights, however, that come to mind.

The last decade has been full. Within my life and the small sphere I orbit, these last ten years are noteworthy for the people I am fortunate enough to call family and friends - for many, the line between the two is impossible to discern. My community, which spans Alaska, Outside, beyond the National boundary- but is most prominent in Homer and the greater Kenai Peninsula - is full of people that inspire me and fill me with awe every day. I moved to Homer, Alaska, a little over a decade ago in search of a community. I found it.

This last decade has been full of incredible, human-powered adventures. I have seen more of Alaska under my own steam than I would have imagined possible. The thirst for more exploration, discovery, and for deepening my connection to this remarkable Arctic state grows stronger with each expedition.

Food has been noteworthy for me over the last ten years. Subsistence gathering is something I grew up with and have never taken for granted. But, my desire to learn more, become more efficient, to preserve with care and intention, to share, to work together, to feel truly nourished has risen to top. Thankfully, masters surround me.

New disciplines and passions began creeping into my life about a decade ago and they are now all consuming. Learning to create content is a boundless joy. I’ve only just begun to scratch the surface. I am in love with learning how to further hone my tools.

This last decade has been a sobering time in my life too. I have become acutely aware of the crisis our species is in and the devastation we are senselessly foisting on the biosphere that supports us. It may appear to some that I am an angry person. As a rule, I am not. However, anger is an emotional tool I am not afraid to use. If over the last decade I have appeared angry, it is because I understand how lucky we all are. I understand how valuable wilderness and the nutrition it provides me is. I understand that community is the remedy to society’s ills. I understand that freedom is more than bumper sticker or an empty campaign slogan. I understand that perpetual growth on a finite resource planet will destroy all that we know and love. Senseless destruction of our garden, which is surrounded by the lonely vacuum of Space, is anger inducing. We should all be angry.

As an atheist, I make no claims about how the future will unfold or what the next decade will offer. For my part, I will, however, continue to surround myself with people I admire. I will continue to skirt the boundaries of the possible in the backcountry and keep seeking new wilderness experiences. I will marry my best friend and spend the rest of my life learning, sharing, adventuring, debating and loving with her. I will continue to be loud about senseless destruction and wanton waste of our finite resources. Anger, with love firmly grasping the hilt, is a tool I am still learning to wield and I expect to have to use it. I predict that I will be angry over the next decade but I would love to be proven wrong.

Happy Winter Solstice, dear ones. May your coming decade be full of passion for what we know and love.

On the north side of the Alaska Range, I skidded and bounced down the Dalzell Gorge struggling to keep my expedition-loaded fat-tire bike upright. Mounds of frozen dirt and icy roots flung me sideways and I squeezed both brake levers, trying to stay on two wheels and not wrap myself around a tree. Suddenly the decline steepened, I spotted a glimpse of bare ice ahead, and let off the brakes to avoid skidding out.

Finally the trail leveled out into a meadow blanketed in crusty snow. The frosty branches on the black spruce trees glistened in the morning light. I lowered my bike and yanked out my camera. A dog team was behind me, coming fast, and I wanted a photo. Through the forest above me I could hear the dog driver gently encouraging his team to slow down. “Wooo. Easy....easy. Good girl.” I flipped on my camera and knelt down, finger on the shutter.

After thousands of years of being Alaskans’ most unfailing means of winter transportation, lifeless internal combustion motors have almost entirely replaced dog teams. Sport and competition have become the stopgaps for widespread utility. The Iditarod, Yukon Quest, and many other mid-distance and sprint races throughout the state have helped keep mushing and our lifeline to history alive.

“My sled is trashed,” the Iditarod musher said as he and his 14 dogs blew past me in the meadow. The conditions in the gorge had been ideal on my studded-tire fat-bike, but the frozen dirt, rocks, and patches of off-slope black ice had been hell for the dog driver. Following their progress through my camera’s viewfinder, I could see chunks of UHMW plastic and shattered fiberglass that had rattled loose and broken. Unfazed, the team of stunning husky’s maintained their steady clip down the trail toward Rohn.

A couple hours later, I pedaled into the remote Iditarod checkpoint, which consists of little more than a solitary, well-built log cabin adjacent to a gravel landing strip. Only a few of the Iditarod’s fastest mushers had made it this far, and each of them was ready for a rest. I found Jasper, the race marshal, and asked him if he needed a volunteer. “Absolutely. You can set up your camp on the airstrip. We need folks to lead the teams into the yard, and there are camp chores ‘aplenty.”

Not long after the first Iditarod race to Nome in 1973, Joe Reddington Sr. began encouraging other user groups to utilize the trail, too–including, eventually, winter bicyclists. For decades, a sub-culture of hearty souls traveled from near and far to participate in the Iditabike and later Iditasport–human-powered races on the Iditarod Trail. These events were the catalyst that helped spur innovation that finally led to the modern fat-bike.

My captivation with mushing came at age 5. Seasonally, my family made the drive to Anchorage from our home in the Wrangell Mountains to refill depleted provisions with store-bought goods. On one memorable trip, my father took the family to watch the film Spirit of the Wind about sprint mushing legend, George Attla. A year later, at winter carnival in Tok, I stood star struck in my oversized beaver parka, when my father pointed and said, “That’s the real George Attla.” I had my first hero.

Watching a team of well-trained dogs respond to nuanced and subtle commands of a compassionate and dedicated driver is profoundly emotive. It’s easy as a spectator to get a glimpse of these hard-won animal and human connections at the start or end of a dog-mushing event. Only the most calloused onlooker would not be moved by witnessing the frenzy of pre-race excitement as it becomes channeled in the starting chute. When everything goes right, one can observe the genesis of magnificent unison as a team of 15 become one mind, pursuing one objective.

Nothing, in my experience, however, beats seeing a dog team in the wilds of Alaska–far away from the noise and bustle of the crowd. A fat-bike is the perfect instrument to bring you there.

Over the years, I have gleaned evident lessons from the trail. There are three that rise to the top. As a non-musher, regardless of your discipline or sport, always yield to dog teams. A snowmachiner, skier, or cyclist has a much easier time pulling off to the side, and an easier time getting going again. Always leave a shelter cabin along the trail in as good a condition or even better than when you found it, as these shelters can save lives. The last one is subtle but is perhaps the most important, because if it is observed, everything else will follow. Never shake a fellow trail-users hand with gloves on. Even in minus 30º, it’s imperative to shake hands along the trail with bare skin and honest, human contact. The warmth that this simple and long-standing traditional gesture offers is greater than any momentary discomfort.

I awoke before dawn after the previous long day and even longer night at the checkpoint in Rohn. Noticing that the cabin’s water supply was running low, I grabbed the orange plastic sled with two screw-top five-gallon buckets and drug them a half a mile away to the chopped-open hole in the frozen Kuskokwim River.

Throughout the previous 18-hours, I had helped dozens of mushers lead their teams to their straw beds and had shaken hands and conversed with many giants of this sport. The race marshal and veterinarians never slept, but tired dogs and trail-worn drivers curled into little balls and took their well-earned respite.

All was quiet as I admired my surroundings in the still, crisp air on the north side of the Alaska Range; the faint glow of pre-dawn light silhouetted the proud mountains to the east. In my moment of quiet reflection, a lone husky from the dog yard let loose a stirring howl. Instinct and abandon took hold of me, and I responded in kind.

Deadhorse to Trailhead

Over 20 years ago, my friend and mentor, Roger Cowles, told me a story about being in Utqiagvik (Barrow) and being able to ski to Wainwright in one continuous push – a distance of over 100 miles. Roger had been in Utqiagvik to help with a bowhead whale survey. The snow, while he was there, underwent a thaw and freeze cycle, making the surface rock hard; he saw an opportunity to ski far and fast. Roger’s story infected me all those years ago. Since then I have hoped to be available to attempt something similar on the Arctic Slope of Alaska with a fat-bike.

Early in the morning on the 6th of May, after pouring my first cup of coffee, I checked my Facebook and saw photos from my friend Qaiyaan, an Utqiagvik buddy. He’d been out on the country traveling by snowmachine and his images revealed what looked like ideal conditions for fast travel on snow over great distances. I immediately messaged him to confirm. “Yea dude, this is right snow conditions, u could have bikes for miles and Fucken miles,” came his response.

Now all I needed was a partner willing to drop everything and join me on a fools adventure. Hey, want to cross a couple hundred miles of the loneliest region of Alaska? No one has tried it on bike before, the snow may melt out at any minute, there are bears, we have to get past the hyper-secure-industrial-oil-lease-lands with a firearm and once we are underway we won’t see a soul. And we need to leave day after tomorrow. It should be fun.

Chief steward of the RV Sikuliaq and my long-time BFF, Mark Teckenbrock, was home in Seward with a couple weeks remaining between hitches. He took the bait and enthusiastically accepted the quixotic invitation.

Two days later we were on an Alaska Airlines jet to Prudhoe Bay with our loaded bikes and tummies full of butterflies.

In Deadhorse—the industrial community on the North Slope of Alaska, full of man-camps and mostly out-of-region-oil-company-workers—Mark and I stood out like sore thumbs. Many people cycle up to Deadhorse along the Dalton Highway in the summer months but in the still-wintry month of May, our fat-bikes and Patagonia garb looked out of place amongst the Carhart-and-steel-toed-boot uniform of the oil-filed workers.

After putting our bikes together in a truck-warming bay at the airport, we rode across the street to the Prudhoe Bay Hotel. We had no idea how we were going to get past the secure oil fields and to the beginning of the trail we planned to follow. We hoped to get some information. On wilderness expeditions, I have come to depend upon local knowledge. In this instance, we were beginning our trip in a bustling community where no one is local and none had information. “CWAT Trail? Never heard of it.”

The hour was late; we’d both spent the previous evening frantically packing and had risen early to drive to Anchorage. We decided to get a meal and a room at the hotel and try to figure out this stubborn and atypical hurdle in the morning.

“Are you guys from Seward?” the security guard asked us as we walked into his office the following morning. “Yes,” we said. Although neither Mark nor I recognized him, we saw this as a sign that we had an above average chance of getting past the security impediment. Our hopes were quickly dashed. “Not a chance,” came Zack, the security guard’s, reply, after we explained what we were trying to do. “The only way to get through the oil field is if you have an identification badge for both BP and Conoco Philips, which you’d have to fly back to Anchorage to get.”

Zack was willing, however, to see what he could do but he gave little reason to hope. He called one superior after another to let us explain our situation and need over the speakerphone. From the higher-ups we received variations on the theme of “No,” and “Hell No.” Our prospects were looking grim until our helpful security guard told us of one option that remained: a transport from a North Slope Borough employee.

At the main borough office in Utqiagvik, Brower Frantz answered the phone. After explaining our situation and who we were, Brower told us that he might be able to help us reach the trailhead beyond the secure oilfield areas. A few hours later we were in a pickup truck, with our clearances and a security truck escort, in front, carrying our firearm, which we’d brought for bear protection. A more surreal beginning to an expedition I have never met.

Lost and Found and Lost and Found Again

After passing through the BP oil filed lease area we met a Conoco Philips security driver and again gave him our gun to shuttle ahead of us. “They do this for the locals, too,” Tom Martell, our gracious borough driver told us. “Even bb guns are forbidden.” Typically, I prefer carrying bear spray over firearms for bear protection but the North Slope is a windy place. Brown bears were awake from their winter hibernation and although we’d be traveling on an inland trail, polar bears exist in this region. My friend Billy had lent me his 4” barrel 500 Smith and Wesson revolver – the largest handgun they make.

When we reached the end of our industrial road trip, the two trucks stopped and we got out. A post-apocalyptic Mad Max movie script swirled in my mind. We thanked Tom, unloaded our now dusty bikes from the bed of the truck and waved goodbye as they drove away.

The profound and ominous sense of holy shit, we are fucking out here was quickly erased once we hit the trail. The conditions were exactly what we’d hoped they’d be – rock hard snow, verging on ice, with a strong easterly tail wind. The temperature was in the mid-20s; the afternoon sun was on our faces and my trepidations evaporated into bliss as we rode along at top speed.

The CWAT Trail is a recent undertaking by the North Slope Borough. For the last two winters, the borough has groomed and maintained an overland route from Utqiagvik to Deadhorse to allow residents an alternative for bringing vehicles or supplies to the extremely remote and most northerly community in the United States. Beginning in February, the route is punched in with piston bullies. Groups of Utqiagvik residents drive trucks and cars up from Fairbanks or Anchorage to Deadhorse, and then over the tundra on this nearly-300-hundred-mile fleeting snow trail. By the time we began our trip all the caravans had wrapped up for the season and all the markers had been removed. The trail, however was obvious as day.

Before leaving home, I’d contacted the borough and told them of our plan. I talked first with search and rescue and then with someone from the land-use department. They graciously approved our non-commercial journey and had sent me a low-res satellite image with the route overlaid on it. The majority of the trail is straight west but then turns north for the last 70ish miles. In the corner of the image, text read, “Proposed 2019 route.” As Mark and I sped along, neither of us thought much of the fact that we were beginning to trend south. We’d seen no other trail and the one we were on was a veritable highway.

Although we’d not crawled into our sleeping bags until after midnight, I woke with a start at 6:15 and fired up the MSR stove to start melting snow. With so much ground to cover before the next thaw, which could come any time, we needed to make the most of each precious day.

Minutes into our early morning ride we encountered snowdrifts that entirely covered the trail. Riding over drift snow is energy intensive and slow going on a fat-bike. For five miles the drifts persisted, as did our confounding southbound compass heading. We were beginning to worry that we’d somehow gotten onto another trail but kept justifying our foreword push because neither of us had seen any sign of another trail. “Maybe there is open water on the Colville River and they re-routed to cross it further up?” I offered. Around 2:00 in the afternoon we began to worry in earnest.

“Yes, you’ve gone too far south,” our friend Hig confirmed over our InReach. He sent us coordinates, as did our friend Qaiyaan in Utqiagvik. We were on an oil company exploratory trail, headed for the Brooks Range. Somehow we had missed the trail. By the time we were certain that we needed to backtrack, a strong wind from the northeast had manifest. Knowing that the wind was supposed to blow itself out by morning, we set up shelter and sat it out.

Once we made it back over the snowdrift section of trail, the following morning, and back to our first camp, we saw a split in the trail that we’d missed the first time. We knew it wasn’t the trail we ultimately wanted but it headed northwest rather than northeast, as the trail we’d followed in did. Taking this trail, we reasoned, would be better than the original one. As long as we continued north we were bound to encounter the east-west CWAT trail we wanted, and this trail would veer us more to the west. Within an hour we’d found what we were looking for – the westbound CWAT. Once we were lost but now we were found. Our confidence had taken a blow and we’d used up precious fuel but we felt our spirits lift as we began to zip along again, in the right direction.

My mind had just begun to relax a little when another text came through Mark’s InReach. We’d been on the westbound trail for six miles when our friend from Utqiagvik sent a message saying we were, yet again, on the wrong trail. I punched in a short and succinct reply - “Fuck!” Sure enough, the GPS waypoints showed that we were south of the trail by about 5-miles. “There should be a Y,” he said, “where they merge.” He sounded uncertain; we were crushed.

We continued west for another mile until we saw a wide-open patch of terrain. Tentatively, I veered my bike off the trail to the north. The open snowfield barely supported my weight atop my bike so we let out tire pressure to what I consider stupid-low and we began hunting through the open tundra for the CWAT chimera.

Hours later, exhausted and demoralized, we gave up. We’d stumble-fucked through bare tundra, slushy bogs, and open snowfields and were further north than all the waypoints. We were in terrible terrain for a trail to be. To the west, as far as we could see, was a pasture of willows poking through the snow - horrible ground even without a bike to travel through. We pitched our shelter and drank Mark’s celebratory airplane whiskey. All seemed lost.

“We looked and looked but can’t find it. Pretty sure we were on CWAT but now r worried about not having enough fuel,” I texted to my friend Qaiyaan in the morning. “I’ll see if my buddy from Nuiqsut can run you out some gas. You got some money to pay him?” From where we were, the village of Nuiqsut was about 10 miles away in a straight line. Before replying to Qaiyaan, Mark and I had a discussion. Although it seemed like our trip was off to a shaky start, I lobbied that we take the opportunity to re-fuel and carry on. He agreed.

“My buddy Thomas Napageak is a hella AF hunter,” Qaiyaan said in his last text. Good, I thought. Hunters know their way around the country and we needed some fucking answers. An hour later Mark and I were slowly making our way back south when we saw Thomas’ snowmachine approaching. As he drew near he ascended a bluff and it looked as though he may miss us. “Plug your ears,” I told Mark. I took the 500 out, pointed it into the air, as far away from my ears as possible and fired a shot. My right ear rang and I went half deaf for several minutes but the cannon blast had worked.

“Yea, you were on CWAT,” Thomas said. As Mark filled our fuel bottles with the white gas, Thomas snapped a photo with his smartphone and walked above his snowmachine holding it above his head to find a signal. “You posting that?” I asked. “Yea. I wrote white gas for white guys,” he said, and we all busted up laughing. After being lost and found and lost and found again, we had fuel. Furthermore, our expedition had been given a name – White Gas For White Guys.

Two Days of Near-Bliss

“We are exactly atop Hig’s waypoint,” Mark said as we stopped on the west side of the Colville River to drink from our thermoses and eat a bite. Over the night it had snowed and for the first time on our trip there had been no wind – rare phenomena in the Arctic. The inch of light snow atop the hard trail slowed our speed some but the conditions were still way above average for efficient snow travel by bike.

West of the Colville, we entered terrain unlike any I have ever experienced – absolutely flat, white with snow, and yet beautiful beyond description. Ptarmigans cackled and the sun shone strong as we rode on mile after mile. “This may be the closest we’ll ever get to experiencing what it’s like to be on the moon, eh?”

For two long days we traveled toward our destination, uninterrupted by route-finding or serious decision-making. Signs of the impending spring breakup were everywhere though. Each day we saw more and more migratory geese, swans and cranes making their way to their spring nesting grounds and each day more of the bare tundra exposed itself.

We were west of Arctic Alaska’s greatest lake, Lake Teshekpuk, when it began to warm up above freezing and the trail started to become sloppy. The new snow that had fallen when we were still east of the Colville was now, also, becoming a pain. During the heat of the afternoon, the skiff of snow melted but not entirely. As the snow re-froze, the surface morphed into a crispy verglas that insulated the softer snow beneath. We took out more tire pressure and nosily crunched onward.

Although it was only 5:00 PM, we decided to camp early on our third afternoon since leaving the Colville. “Let’s set the alarm for 2:00 AM and cross our fingers that it freezes tonight.” As we made coffee, the inside of our shelter, at 3:30, was still wet with condensation and outside we could make slushy snowballs. It hadn’t frozen. A damp and chilly fog settled in as we rode away at 5.

“How are you guys doing?” Came a message from Brower Frantz in Utqiagvik. We didn’t know what to say.

As we took more and more tire pressure out, we slowed to nearly walking speed and often had to dismount to push beyond the worst of the rotten patches. By 11 they were all rotten patches. Crossing a channel of the Ikpikpuk River, I stomped on and compressed the slush to keep my calf-high over-boots from being overtaken with the flowing open water. West of the river we found a dry patch of ground and sat down to discuss our options.

“You are super close to my cabin,” Qaiyaan’s InReach message said. He sent us coordinates and told us to head there. “It’s only a couple miles from where you are. There’s food and beds. I’ll come get you tomorrow evening.”

Saved

We were enveloped in thick pea soup fog as we sat on our little dry clump oasis on the shore of the Ikpikpuk. “We should reply to Brower, eh?” Mark punched in a response to his question, how you doing. A few minutes later, Brower replied and said he’d come retrieve us. This guy, whom we’d never met in person, was willing to finish his work day and head out into the fog and rotten snow for a 3 to 4 hour snowmachine trip to our location and give us a ride into Utqiagvik. “Quyanaq*. Thank you, Brower.”

For the first time on our trip we had access to dead willow branches and bits of driftwood. We built a fire to help ward off the damp and chilly air as we waited. Late in the evening, Brower sent another message, “Still getting everything together. Will leave town around 11.” Mark and I had started our day at 2:30 so we decided to set up the shelter and get a few hours of shut-eye.

We sprung awake as the sound of Brower’s machine drew near. We greeted him with groggy enthusiasm but needed a few minutes to pack everything away for what was bound to be a bumpy sled ride. He’d brought several 30-gallon containers of fuel for his cabin, which was less than three miles from our location. “I’ll go drop this off and come back in a minute,” he said. By the time he returned we were packed and bundled up, wearing every item of clothing we’d brought.

At our first pit stop, Mark and I pulled out our sleeping bags. When we resumed the trail we both crawled inside them, boots and all. Our goggles quickly misted over from the fog but we hunkered down and took in the experience.

Utqiagvik

The new day was in full swing when Brower pulled his snowmachine into Utqiagvik. The day before the entire community had melted out and the streets were bare gravel and mud, and slicks of water pooled in every depression. City workers were busy throughout the community pumping water away from homes and streets.

As Mark and I unpacked ourselves and bikes from the sled, Brower went inside his house to change. When he came out he had news: “They just caught a whale right in town.” The open sea was less than a couple hundred yards offshore – an eerie, unnatural and obvious indication of our global climate crisis. Until very recently, the sea ice extended 20 or more miles out and whalers had to make trails through and over the hummock ice to set whale camp. “We’ll meet you at the Top of the World Hotel for breakfast,” we told Brower and gave him money for gas and our best guess at the value of his time.

All three of us looked haggard as we stumbled into a booth at the restaurant. Our poofy eyes and incoherent conversations helped inform our waiter that we wanted coffee and to keep it coming.

Reflection

Many obvious reflections can be made about our trip to the North Slope but none of them interest me too much. The main take-away for me is that I was able to experience an environment that I have been intrigued by for longer than I can remember, and it was more incredible than I could have imagined. This trip and experience gave me a small taste of the region’s moods, its wildlife, and, most importantly, its amazing people.

There are so many things that go into trying a new route with atypical equipment like a fat-bike but nothing teaches me more than giving it a shot. What we know now verses before we began is immeasurable. I plan to use this newfound wisdom to the best of my ability for next time.

*Quyanaq = Inupiat word for thank you

Kim and Bjørn bathing in sunset light near Hotham Peak.

After a winter of warm weather here in southern Alaska and watching as the northwest Arctic got hammered by six weeks of snowstorms, the forecast for our Kobuk traverse looked somewhat promising. The Bering and almost all the Chukchi Sea ice is gone. This means there is more warmth and more moisture where it otherwise should be cold and dry. The conditions when we left to fly north, however, looked encouraging. Maybe winter would return.

In Kotzebue, our friend Asuaq—a lifelong resident of the region, met us at the airport. After we assembled our bikes and strapped gear on, we rolled outside and felt the air and the surface of the snow. It was not as cold as one would expect for this time of year at this far-north latitude but it would do.

The following afternoon, after visiting with the good people at the Northwest Arctic Borough and our favorite native craft store—Sulianich Art Gallery—where I bought a trappers hat—we hit the trail. It was apparent that we were atop six weeks of snowstorm accumulation but the days were clear, people had been out and the trail was more than we could have expected. We were riding. We were underway.

Three days later, we ground hard through soft snow and small drifts into the second village on our route—Selawik. Our intention was to find someplace to stay for the night and to make an early break the following morning for a shelter cabin, which we figured at our slow pace would take a full day to reach.

Weeks before we began, people had warned us that there was a lot of overflow and open water on the Kobuk River. Everyone we’d met and interrogated about conditions offered us the same report. Since our arrival, however, the temperatures had been cold and we hoped that by the time we reached Ambler and began to come down the river, that more people would have traveled that way and the water would have frozen. The evening we pulled into Selawik, the air became heavy and the wind was warm.

After days of rosy cheeks, squeaky snow and a frosty beard, I was unprepared for the impending reality. Throughout the entire region rain and above freezing temperatures were in the forecast. Outside, we could feel it coming. From Selawik, there are options. There are other trails. But as we checked, every direction called for the same – warm and wet.

On winter fat-bike expeditions, we are not prepared for wet. We are prepared for cold. Not to mention that when deep snow thaws it becomes unconsolidated and entirely unrideable. Thankfully school was out and no one other than Kim was present in the library to hear me curse and moan. All of that, ‘you get what you get and don’t get upset’ talk is nonsense. She shushed me all the same.

The following evening, on a comfortable couch back in Kotzebue, after a fantastic meal of caribou and even better conversation with our friends Seth and Stacey, I started to doze off. With the book, ‘The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F**k,’ still in my hands, my mind returned to the trail. The sun was low. I was bundled in my fur hat and standing over my bike on a cold winter trail. I came back to and felt a pang of remorse. Losing winter and the freedom to explore is something I do give a f**k about. I set the book down and tried to be thankful for the wonderful, if much too short time we had had.

Bright lights from an approaching vehicle cast a long shadow ahead of me. I was riding my bicycle on an icy road; the light grew brighter and my shadow more defined. I felt apprehension as the vehicle advanced from behind, at full speed. With no shoulder to ride in, few options appeared available. My fate was in the hands of the approaching driver. This was my first winter commuting to work on a bicycle, nearly 20 years ago.

I have owned vehicles ever since it has been legal for me to drive. That winter, it was a Subaru, which, for my money, has always seemed to be one of the best year-round cars for Alaskan conditions. However, for one year, I made a pledge to myself not to drive it. I was conducting an experiment on myself. I wanted to test—and not because of a court order—what life was like not driving for an entire calendar year.

Learning to trust often takes time and learning to trust carbide studs on bicycle tires is no exception. I was living in Seward the winter I bought my first pair of good winter bicycle tires and committing to my year of no driving. What the studded tires were capable of was still theoretical to me.

Winter road conditions in Southern Alaska fluctuate weekly, daily, and sometimes hourly. The conditions during my first scary ride with the brand new tires were of a type anyone who lives in Southern Alaska has seen many times: snow, which has melted, compacted, re-frozen and is then hastily plowed. The road surface was exposed but retained a thin film of ice. The shoulder to the right, including the white line, was a jumble of chunky ice, deposited from the first-pass of a DOT road grader.

At the last second, I realized the driver was not making allowance for me. Even though there were no oncoming vehicles, they were not swinging wide, nor were they reducing speed. Anger welled within me. How could someone be in such a hurry that they were willing to compromise my life? My blinking red taillight was flashing on and off, indicating that an actual human being was lawfully using the road, too.

Impact seemed imminent. My survival instinct took charge and without actually thinking, I instantaneously weighed my options. Crashing into the jumble of ice, piled by the grader onto the shoulder, was a better option than being hit by the car. I veered right.

To my astonishment, the tires bit into the ice. In fact, they seemed to chew it up, spit it out, and ask for seconds. The car passed, my shadow evaporated and, except for the beam of light from my headlamp, I was engulfed again in peaceful winter darkness. I continued to ride over the broken ice, experimenting with this newly discovered traction. Incredible, I thought. Carbide studs are amazing!

Since my one-year of strict no driving rule passed, I have continued to commute by bicycle, a lot. In the intervening years, I have experienced all sorts of winter conditions and have come to the firm conclusion that there are few circumstances modern bicycles—which can include mountain bikes, fat-bikes, touring, and commuter bicycles—properly outfitted for winter, cannot handle.

Winter is coming. With winter comes darkness and, for many, with darkness come apathy, depression, gluttony, and dread. Few things, in my experience, defeat depression better than suiting up, regardless of the weather, and riding a bicycle. At first, riding a bicycle in inclement weather may seem like a chore but eventually it becomes a vigorous addiction.

“You poor thing. You must be miserable,” people say to me, as I lock my bicycle outside a store or the movie theatre on a cold January night. If only they knew, even a sliver, of how satisfied, how good, how not depressed I actually felt. “Do you want a ride,” I am often asked. Never!

In the nine years I have lived in Homer, conditions for year-round cycling have improved. Homer Cycling Club developed the Homer Shares The Road education campaign. This campaign makes the obvious case for being aware of all user groups, emphasizes the law, and reminds our citizens of the kindergarten-age ethic of sharing and taking care not to hurt others. Even though there is no hard data to prove my case, I have noticed improved attitudes between motorized and non-motorized interactions, since this education campaign began.

Besides a good pair of carbide-studded tires, the other things essential for successful and enjoyable winter bicycle commuting are: lights (both front and back), fenders, rain gear, good winter boots, helmet, and a positive mental attitude. It is entirely worth it to splurge, whenever possible. My advice to anyone who asks is: spend money on the best and most appropriate equipment. High quality gear, if you can afford it, will work better, last longer, and improve your experience. The more you ride, the cheaper the investment becomes when you factor how much you are not spending on fuel. The value added to every day of your life is incalculable.

Winter can feel oppressive in Alaska. Beat back against those feelings of dread and gloom by engaging with the natural world on a daily basis. Breathe the cold air. Feel your body generate heat. Show up to work with rosy cheeks full of life, vitality, and oxygenated blood. You won’t regret it.

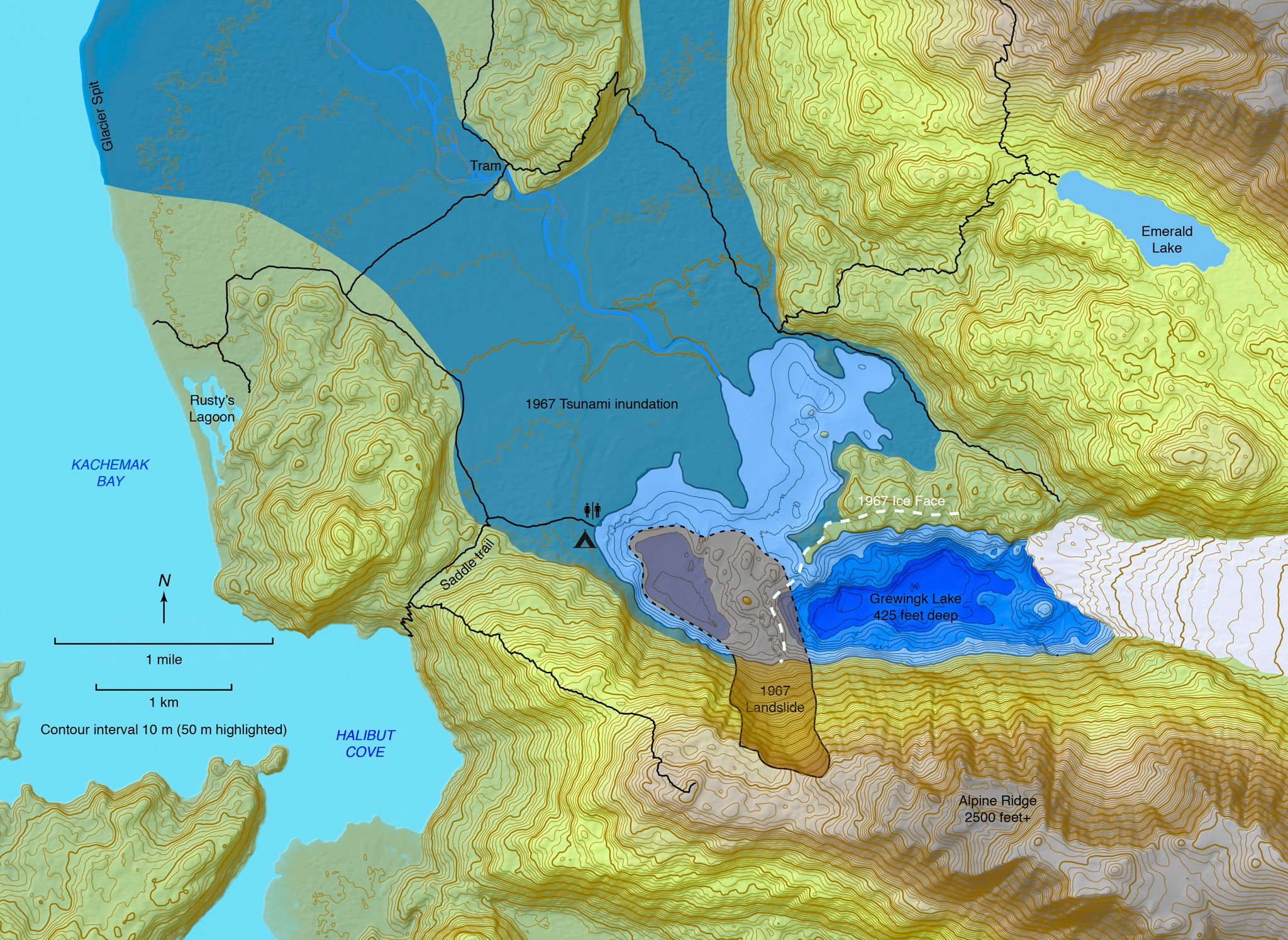

Map of the Grewingk Valley by Bretwood Higman

This article originally appeared in the Homer Tribune.

Imagine hovering in a helicopter above Grewingk Glacier Lake, in Kachemak Bay, fifty years ago. From this safe vantage, you watch as 80 Empire State Buildings worth of material, slowly dislodge from the steep slope above the lake, and then let go all at once. Cleaved from the surface, you see the unfathomable volume of material gain momentum. By the time the deafening roar reaches your ears, the 110 million cubic yards of rock has thundered into the lake, sending a wave hundreds of feet into the air. Craning your neck, you watch this fast moving bulge of water slosh over the outwash plain, uprooting alders and mature trees, carrying everything in its path all the way to Kachemak Bay, more than four miles distant.

You just witnessed a suite of natures most destructive and incredible phenomena—a landslide generated tsunami.

This may seem like a crescendo scene from an apocalyptic Hollywood movie, but last October marked the fifty-year anniversary of the Grewingk landslide and tsunami.

No helicopter hovered in the air and thankfully no one was in the valley that day. However, many in Homer and nearby Halibut Cove heard the crash and later witnessed glacier ice in Kachemak Bay. Homer residents were able that fall to salvage trees for firewood that washed ashore onto the Homer Spit.

This event has captured the attention of two local geologists, who worry another landslide and tsunami could occur in the same area with similar, or worse, devastation.

“The rock all along the mountainside is highly fractured and faulted, as is the rock generally in the Kenai Mountains,” geologist Ed Berg said about the slope above Grewingk Lake. “Major rockfalls or landslides could probably occur anywhere along the steep slope of the mountainside.”

Seldovia resident and tsunami hazards expert Bretwood Higman added, “The combination of steep slopes and weak rock is the perfect recipe for a big landslide. Additionally, the 1967 landslide shows this area has the potential for very large landslides, and this potential may be all the greater now, since the glacier has retreated a lot in the past fifty years.”

Throughout coastal Alaska, landslides, some of which have caused massive tsunamis, are occurring with increased frequency. Steep mountain valleys, fjords, and bays that have, for many thousands of years, been full of glaciers have seen rapid retreat over the last fifty years. This has led to slope instability in many areas. Glaciologists and geologists call this process, glacial debuttressing.

“The slopes above Grewingk Lake are notable because they are much steeper than most slopes in the area, and they're not more strong,” noted Higman. “They probably are so steep because they were supported by the Grewingk Glacier until recently, and because the glacier has been actively undercutting them. The combination of steep slopes and weak rock is the perfect recipe for a big landslide.”

In June, Berg, Higman and the American Packrafting Association organized a human-powered research expedition to Grewingk Glacier Lake, hiking over the trail with a flotilla of packrafts and some low-budget tools.

One of the goals of the group was to better understand the depth of the lake. This information is key to understanding the potential for another tsunami.

For the trip, Berg engineered a simple 1x4 contraption, which he affixed to the stern of his packraft. From this device he mounted a borrowed sonar fish-finder to measure and record the lake bottom depth profile. Others in the party used less sophisticated instruments to measure lake depth from the platforms of their packrafts, like a handheld sonar depth gauge or weighted lengths of string.

The deepest spot the team discovered—490 feet—was near the glacier face and the average depth below the potential landslide slope averaged 360 feet. “We were surprised that the lake is so deep,” said Berg. For a landslide tsunami, deeper water means greater hazard. The entire volume of the landslide could end up beneath the water‘s surface—creating a much bigger wave. Deeper water absorbs more of the landslides energy, converting it into a bigger, more powerful wave.

But how likely is such a landslide? Berg and Higman both agree that further study is necessary, including a detailed survey of the ridge above the lake. “In particular,” Higman says, “I'd look for roots that are stretched across cracks, or signs of blocks that have shifted down as cracks opened below them. If such signs are apparent up there, that would be a "red alert" situation, suggesting dramatic action like closing trails.”

Higman would also like to see computer modeling of landslide tsunamis to assess areas within the valley, which are most at risk for visitors to the area. Furthermore, computer models could resolve the potential for marine tsunamis in Kachemak Bay. “The marine tsunami risk is likely very minimal,” says Higman “but may be relevant since even a small marine tsunami could be very damaging to the Homer Harbor.”

Thus far, Berg and Higman have been aided with small equipment loans and organizational support from the American Packrafting Association but the two are working without funding or institutional backing.

“We would like to see some monitoring program put in place,” says Berg “that could provide timely warning of a future collapse and tsunami.”

“University researchers could be great, especially if they worked with us locals,” said Higman. Adding, “I'd like to see some funding to support someone to take the next steps, including assessment of the hazard, public outreach, investigating monitoring, [and] coordinating different research efforts.”

Statistically speaking, there is no good reason not to visit Kachemak Bay State Park’s magnificent treasure, the Grewingk Glacier. It’s not advisable to camp on or near the lakeshore but the likelihood of a cataclysmic event occurring during a day hike through the park is quite low. No one can predict when or even if there will be another landslide and tsunami. As our climate continues to warm, the research and study of these interconnected phenomena is wildly important—as important, perhaps, as visiting an Alaskan glacier.

-Bjørn Olson

Standing atop a snow drift on the sea ice of Norton Bay.

Story originally published in The Radavist.

March 1998 - Behind me, a strong and gusty north wind stung my legs. I sped across a rock hard snow trail, atop frozen sea ice, effortlessly. My modified mountain bike with Snow Cat rims and two and a half inch wide tires was shifted into the highest gear. With each gust, the fine crystalline snow swirled around the trail, blowing past me and over the polished glass surface of the exposed sea ice, in hypnotic patterns. In front of me and to the right sat a lonely and distant mountain cape. To my left was the shallow arc beach of the Norton Bay coastline, several miles away.

Stories of snow-machiners riding into unseen open leads of water never to be seen again circulated through my mind. The uneasy fear of being offshore and alone in an alien sub-Arctic environment, with very real threats to life pushed down further as joy bubbled up.

I hit a small pressure ridge of ice, felt my front tire leave the surface and bunny hopped my bike into the air. An uncontainable whoop erupted from my lungs and I hollered with abandon into the lonely winter vastness. Visibility was fantastic but the orange sun was low. ‘Would I make it across the ice and to the shelter cabin before dark,’ I wondered. At this fast pace with the accompanying tail wind it seemed certain.

As the sun continued to drop and the pink and orange glow of the impending sunset settled in, a strange thing began to happen: the cape to my right began to change shape in an incredible and surreal way. At first, the pointy top of the summit distorted just a little but then it grew into a taller and more round shaped bubble. My mind struggled to make sense of what I was seeing. As I rode on, staring transfixed, the cape morphed further until finally a perfect mirror image of the conical peak swelled upward into the sky, doubling in size; bewildering my senses.

Over the roar of the wind and the flapping of my nylon hood, I could hear the high-pitched whine of a fast approaching snow-machine coming from behind. When it caught up, the driver stopped. “Everything okay,” he asked, after removing his ice-encrusted facemask. “Yes, but what is that?” I yelled over the wind and his idling machine while pointing to the hourglass shaped and impossible looking cape, bathed in rich sunset light. “Fata Morgana*,” he said. “It’s a mirage. It happens here a lot, when there is a temperature inversion.”

Standing still, the harsh wind on my backside and legs felt even colder. His definition of what I was observing left me wanting more information but we were both in a hurry to get off the sea ice and out of the wind before dark. He was on the way to the village of Shaktoolik. My goal was closer—a shelter cabin on the immediate shore. We both removed our mittens, as is custom along the Iditarod Trail, shook bare hands, wished each other well, and said good-bye.

An hour later, I sat in front of a rusted wood stove in the shelter and lit a fire. Through the frosty paned window, the last of the pink light fell to starlit darkness. As I waited for the space to warm and for my friends to catch up, I reflected on the past few days: we’d left Nome after watching the winning Iditarod dog teams come in under the burled arch, ridden our bikes down the trail, visited an out of the way hot springs that had been in use by Inupiaq Eskimos for thousands of years, and today I had ridden alone across the sea ice and witnessed the most mysterious and wondrous natural phenomena of my life. Despite stiff-cold fingers and wind-burnt cheeks, my sense of euphoria was cranked to eleven. My home state of Alaska—an ancient land of enchantment and mystery—had charmed me once again.

In that moment, I knew this method of human-powered exploration was for me. The freedom to explore wild and remote places that few ever experience is an innate passion that had, up to that point in my life, been achieved by kayak, skis, and mountain climbing. Exploration coupled with the sheer joy of riding a bike on technical terrain, like sea ice hummocks and frozen tundra, had sealed it. Few experiences in my life compared with the overwhelming sense of gratification I felt that night in the shelter cabin. More of this, I thought. Much more.

In the days of my first winter cycling trip, adventure bikes were rigid mountain bikes with 26-inch wheels. Some shade-tree innovators made custom bikes with multiple rims and tires—laced to one hub—but for the average person, unequipped with welding skills and handy access to custom equipment, few options existed for adventure bikes well suited for wilderness conditions. Anyone who rode on snow trails at that time knew that wider wheels and tires were needed but they didn’t yet exist.

In Fairbanks, a bike shop sold wheels originally made of two rims welded together. This led to the winter subculture rim known as the Snow Cat – which is now considered a plus size wheel. At 44mm wide, it was the best commercial option available. But, because of its double width, it fit few mountain bike frames of the time.

In the era of winter cycling with Snow Cats, a heel test could inform you if a snow trail was rideable. The test involved bringing your foot down with all your force, slamming your heel onto the trail. If it didn’t buckle or break you knew you could ride. New snow, breakable crust snow, wind drifted snow, spring snow and many other soft conditions were entirely unrideable. In those days, winter and off-trail cycling involved considerable bike pushing.

For several years, wilderness cycling took a bit of a back seat for me. Backcountry snowboarding, mountaineering, and expedition kayaking were the staples in my life. Far-flung backcountry expeditions by bicycle, however, never left my mind and in the mid-2000s the cycling industry began to catch on. The fat-bike—an unstoppable idea whose time had come—was born.

An era of unique and creative wilderness exploration has opened up as a result of the fat-bike. Over the last dozen years, the discovery of what this new and evolving technology is capable of has been a consuming source of investigation, inspiration, and discovery. On every trip since my very first, nearly twenty years ago, I learn and experience something new. What four and five-inch tires on modern fat-bikes are capable of surmounting is still a source of near daily revelation.

I am continually seeking experiences like my first winter trip on the Iditarod Trail — moments of private and shared bliss within the natural world; traveling and exploring by human-power, with self-reliant alertness; poised to bunny hop a sea ice pressure ridge whenever the situation arises and hungering for mirages that trick the eye and excite the senses.

* Fata Morgana— (Italian: [ˈfaːta morˈɡaːna]) is an unusual and complex form of superior mirage that is seen in a narrow band right above the horizon. A Fata Morgana can be seen on land or at sea, in Polar Regions or in deserts. It can involve almost any kind of distant object, including boats, islands and the coastline.

Fata Morgana is often rapidly changing. The mirage comprises several inverted (upside down) and erect (right side up) images that are stacked on top of one another. Fata Morgana mirages also show alternating compressed and stretched zones.

The optical phenomenon occurs because rays of light are bent when they pass through air layers of different temperatures in a steep thermal inversion where an atmospheric duct has formed.

Kim McNett unloads her prototype Alpacka raft - the precursor to the Caribou - and prepares to resume biking at the Skull Cliffs in Arctic Alaska.

This gear review originally published by Salsa Cycles.

The Roof of Alaska Fat-Bike Expedition Gear Review

Summer 2017, Kim McNett and I completed the first part of our Roof of Alaska, Arctic fat-bike and packraft trip. We began in the Inupiat village of Point Hope, in the far northwestern region of the state, passed through two other villages—Point Lay and Wainwright—and ended 450 miles later in the northernmost community in the United States, Utqiagvk (formerly Barrow). Alaskan adventurers Daniel Countiss and Alayne Tetor joined us for the first twelve days, as far as the village of Point Lay.

As far as we know, no one has employed a fat-bike in this vast region of Alaska and only a few have done human-powered trips in this region by any means, in modern times.

For the entirety of our trip we were above the Arctic Circle. We cycled over mountainous terrain, tundra, beaches, and riverbeds and, once away from villages, saw little sign of human traffic. We paddled where necessary and pushed our bikes very little. Much to our astonishment and delight, this trail-less wilderness route was attained almost exclusively from the saddle of our bikes.

Each trip reveals new insights into technique and gear and every year new innovations in equipment design stand on the shoulders of the previous incarnations. Below is an overview and review of the equipment we used.

Bike:

Since the fat-bike was first conceived, refinement has yet to cease. In the late 1980s, Alaskan shade-tree bike innovators welded two rims together and laced them onto one hub to provide better flotation on snow trails. Since the mid 2000s, interest in this subculture sport has grown exponentially and innovation has been off the charts.

For our recent fat-bike and packraft trip through Arctic Alaska, I used a Salsa Cycles 2017 carbon fiber Mukluk – the apex of wilderness adventure cycling design. This lightweight bike is an adaptable, do anything, go anywhere machine.

The goal of any fat-bike and packraft expedition, in my mind, is to ride as much as possible. In order to circumvent the myriad obstacles one is bound to encounter, on an untested wilderness route, a bike needs to be nimble, yet comfortable, lightweight, yet durable, and outfitted with the widest wheels and biggest tires available. The 2017 Mukluk is all this and more.

For our Arctic expedition, we stripped our bikes down to their most simple form—a derailleur-less multi-speed drivetrain with one brake.

The drivetrain on my Mukluk consisted of two cogs and two stainless steel rings on Surly OD cranks—30 tooth and 22 tooth. The OD crank is an ideal choice for trips like this as it is easy to pull in the field, the dust cap does a decent job of keeping out dirt and water, and re-packing the bottom bracket bearings are a cinch. I used a Salsa freehub and ran 26 tooth and 22 tooth stainless steel cogs

On a Sram eight-speed chain I installed two sets of master-links. I could quickly add or remove one set and three links that separated the master-links and shorten or lengthen the chain to fit either the big or small ring, as needed. The Alternator dropout allowed me to use either cog when I was in one or the other ring. I used all four of these gear options on this trip. If I were to do this trip again, I wouldn’t change a thing in regards to the drive train.

The 2017 Mukluk is well suited for expeditions and carrying a load. The front fork has three mounting bolts per leg, the down tube is flat on the bottom and therefore an ideal place to strap a long skinny dry bag, it supports a rear rack, and the front triangle, despite having a swale for stand over clearance, has plenty of space for a frame bag due to the steep angle of the down tube.

Our longest stretch between food resupply on this trip was 12-days. When fully loaded, I used two lightweight dry bags on my fork legs and one long, skinny dry bag on the bottom of my down tube to carry food. Daily snacks were carried in my handlebar-mounted feed-bags and the remainder of my food went into my home-made frame bag.

I also used a Salsa Alternator rack, which I typically used to carry one medium size dry bag. Within this bag were my sleeping quilt, sleeping pad, shelter, and clothing. The rack was more useful than a seat-pack because we often had to carry water for more than one day at a time. With the rack, I could strap 90-ounce dromedaries onto the side of the rack as needed.

Our usual strategy, on summer fat-bike expeditions, is to carry a big, lightweight backpack, which we can put all gear and food inside when we are forced to push/haul the bikes long distances. Due to the mostly rideable terrain on this trip, our backpacks were nearly empty and the food and gear fit, with room to spare, on my Mukluk.

Packraft:

Much like the fat-bike, packrafts are currently enjoying a never-ceasing evolution of improvement. Alpacka Rafts have been at the forefront of design and innovation for many years. Alpacka sent us out on this trip with two prototype rafts—Fjord Explorers with a proprietary lightweight fabric, typically used for the featherweight Scout series rafts.

On numerous occasions, I have made the mistake of sacrificing durability for lightweight equipment. On those trips, I end up wasting time in the field on repairs. One of the major debates we are often concerned with before a long trip is where to shave weight and where not to.

Although the fabric on these rafts is less durable than the standard Alpacka raft fabric it more than stood up to the rigors of this expedition. We were, however, cautious with the boats, which is good practice with packrafts regardless.

The prototype Fjord Explorers had few bells and whistles: Cargo Fly zippers, one valve, and four tiedowns in the bow and two in the stern. To shave weight, we opted to forego spray-decks.

This trip involved many short, flat-water crossing but also a handful of 10 to 15 mile open-water stretches. Hull-speed in these instances is a huge asset and due to the rafts increased length we could always achieve full and powerful forward strokes with the bikes on the foredeck. The increased length and pointy bow and stern also kept the boat from drifting a little to the right and left on every stroke, which is unavoidable on shorter rafts.

Within both fat-biking and packrafting there are several sub-disciplines, of which bike/rafting is one. Over the years, I have tried many packraft designs and configurations for long, wilderness cycling traverses, where most of the water we encounter is relatively flat. For this type of trip, a slightly longer raft is ideal but an even longer raft, with a pointy bow and stern is even better. By using the lighter fabric, these rafts weigh less than and roll up to the same size as our previous rafts, which are much shorter.

Shelter:

The Mountain Laurel Designs Duomid is a lightweight two-person, floorless shelter made with sil-nylon. The weight of our duomid comes in around one pound. When packed, it compresses into the size of a large grapefruit, yet, when pitched, two people have enough room to fully lie out with room to spare for gear.

The Arctic summer is famous for insects. Before we left, I sewed a continuous strip of mosquito netting—about 16” wide—around the perimeter of the shelter, which we tucked inside and set gear and sleeping pads atop of. Although this didn’t keep every single bug out, it did do remarkably well and it would be hard to find a lighter weight option.

For four days and nights on this expedition, we encountered incredibly strong wind—gusts over 60 miles per hour. As long as we took care to properly anchor the shelter our Duomid withstood the onslaught handsomely.

For the center pole we used three pieces of our four-piece kayak paddle. We typically rely on natural anchors, which are often more robust and capable at withstanding strong wind than aluminum stakes are.

Sleeping System:

Kim and I both used Therm-A-Rest Neoair sleeping pads and Mountain Laurel Designs Spirit quilts—rated to 28 degrees.

The Mountain Laurel Designs zipper-less quilt is simple, lightweight (23 ounce) and quick drying. It has a fairly roomy foot box, which is held into this shape with Velcro and snaps, and it employs a thin webbing strap to secure the quilt around the sleeping pad. This quilt can also be opened into a rectangle bedspread but for maximum insulation it is best to secure the foot box and cinch the edges under the sleeping pad.

The trick I had to learn is how much to tighten the strap under the quilt and around the sleeping pad. If the strap is too loose, the bag slips from under the pad, letting cool air in. If the strap is too tight, it feels constricting inside the bag. After a few days I had the ratio finely tuned and the quilt worked as designed.

At the beginning of our trip, we had several chilly nights and I often slept in my puffy sweater with the hood up. This sleeping quilt does not cover your head so it is important to have a warm hat and either a vest or a sweater with a hood when you use it near the low end of the recommended temperature rating.

Kitchen:

On summer trips, we typically forgo cook stoves and instead rely on open fires. However, trees do not grow in the Arctic. Before leaving on this trip I knew of only one person who had undertaken this journey by human-power. Alaskan adventurer, Dick Griffith, skied across the Arctic of Alaska in the 1980s. He assured us there would be plenty of driftwood. Only once, while we were traveling overland, were we unable to have a fire or cook a meal.

Cooking and heating water on open fires takes a little more time than using a cook stove but I take great joy in all aspects of this camp chore: gathering wood, lighting the fire, cooking, and drying wet gear. There are few things better in life than reflecting on the day, with a hot beverage and warm bowl of food in front of an open fire. The daily uncertainty, when relying on wood fuel, is something I fully appreciate, not to mention the liberation from carrying an extra piece of equipment and the fuel it requires.

Kim and I carry one 30-ounce titanium cook pot to cook meals in and we each carry one 24-ounce titanium mug apiece for beverages. Beyond these items, we carry one spoon apiece, one Victorinox knife and several lighters.

Pack:

For the last several years, I have used a Mountain Laurel Designs Exodus 58 liter backpack on summer bike expeditions. Cycling with a backpack is, by my estimation, never ideal, but for long wilderness trips they become a necessary evil. The backpack becomes most valuable when the riding ends and long hours of pushing begin. Pushing or carrying a bike with most or all the gear stowed in the pack is more efficient and easier on the body. The Exodus backpack is a fantastic choice for this sort of undertaking. This lightweight (16 ounce), no frills, frameless pack is comfortable, wicks moisture well, and can haul a big, heavy load. When the riding resumes and all or most of the gear is re-packed onto the bike, you hardly notice this featherweight pack freeloading on your back.

Technology:

There were three pieces of technology we carried on this trip: a DSLR camera, a GPS, and an InReach satellite tracking/texting device.

For GPS, we used a Garmin 64. Before heading out, we uploaded topo maps into the GPS unit. Thankfully, our Arctic route was just barely within the coverage area of the USGS topographic map database. We also carried 1:250,000 scale topographic maps, which gave us the big picture. But, for the detailed route finding, we relied on the GPS. One of the things I appreciate about this model is that is not a touch screen. In the past, I have found that the touchscreens eventually become difficult to see. Navigating traditional buttons with wet, cold-stiff, or dirty fingers is also much easier than on a touchscreen. The Garmin 64 is a straightforward, no frills GPS, with all the basic navigation features.

The Garmin InReach has worked its way into the, never leave home without it category. This handheld satellite tracking and emergency texting device allows friends and family to follow your progress and read short updates through an online service called Mapshare. More importantly, though, this small device can send and receive satellite text messages. In the past, the only option for wilderness or maritime travelers to request emergency assistance was with an EPIRB – an emergency locater beacon, which, in Alaska alerts the state troopers, Coast Guard and other emergency responders. Now, with the InReach, if the party is in a bad situation they can text the details to a friend or family member and a more measured, less expensive option can be discovered. We also sparingly use the InReach to request weather forecasts from friends. It is paramount that any person heading into the wilderness be self-reliant, have basic first-aid knowledge and willingness to self-rescue. However, unforeseeable calamities can befall anyone. Having the technology to save a life is worth its weight in gold.

Final Thoughts:

Few places that I have experienced have felt as remote, with the umbilical chord of safety so distant, as our trip in the Arctic. This trip was one of the most demanding and rewarding I’ve yet to undertake. Accomplishing this trip took more than a modicum of luck. It also required sound route finding, good local knowledge, persistent effort, a solid partner and dependable equipment, well suited to the rigors of daily use and abuse. Gratefully, all the proper ingredients, for the fat-bike expedition of a lifetime, accompanied me.

If you happen to find yourself drawn into the backcountry with a bike and packraft I hope you find this gear review useful.

Bjørn poses with a mammoth tusk he found while riding his Salsa Cycles Mukluk fat-bike in the Arctic of Alaska.

For professional photo shoots, stock photography, videography or filmmaking, please email bjorn@groundtruthtrekking.org for prices and quotes.